The gear: one of the oldest mechanical components still in use remains the backbone of motion transmission across nearly every industry. Whether in automotive drivetrains, aircraft gearboxes, robotics, or wind turbines, gears continue to define the efficiency and reliability of power transfer systems. For more than a century, gear manufacturing has been the realm of precision subtractive processes such as hobbing, shaping, grinding, and honing. These processes, refined through decades of experience, deliver micrometer-level accuracy and surfaces smooth enough to sustain hydrodynamic lubrication under extreme loads.

Now, additive manufacturing (AM) commonly referred to as 3D printing has entered this space, promising new possibilities: near-net-shape fabrication, design freedom, topology optimization, material efficiency, and rapid iteration. Yet the question remains: is additive manufacturing truly ready for production gears? The answer, as modern research and industrial practice suggest, lies somewhere between “partially” and “conditionally.” AM is ready for certain gear applications when combined with hybrid post-processing workflows, but not yet ready for high-volume, high-performance transmission gears without significant finishing and validation.

Understanding the Gearmaker’s Benchmark

Before assessing AM’s readiness, it’s important to recall the demanding performance envelope of conventional gears. High-quality gears typically conform to AGMA or ISO Grade 6-8 accuracy, requiring lead and profile deviations below ±5–10 µm, and surface roughness values (Ra) under 0.2 µm on the flanks after grinding or superfinishing. Mechanically, gears are designed to resist contact stresses of 1000-2000 MPa and bending stresses at the tooth root exceeding 400–800 MPa, depending on material and heat treatment. Any deviation in geometry or surface integrity can alter load distribution, initiate premature pitting, or amplify noise and vibration.

Traditional manufacturing methods like hobbing and grinding inherently achieve these precision levels due to stable material microstructures, controlled residual stresses, and predictable machining behavior. Additive manufacturing, however, introduces new variables layer-by-layer anisotropy, porosity, surface roughness, and thermal distortion that challenge these established quality standards.

Additive Manufacturing Processes for Gears

Several AM processes are relevant to gear manufacturing, each with its distinct strengths and limitations. For polymer gears, technologies like Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), and Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) are widely used for rapid prototyping and functional testing. These methods allow designers to verify gear geometry, fitment, and assembly kinematics within hours, using materials such as PA12, PEEK, or carbon-fiber-reinforced composites. However, their mechanical and tribological properties limit their use to low-load, low-speed applications such as robotic end-effectors, medical devices, or instrumentation drives.

For metal gears, the primary AM technologies include Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) also known as Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS), Directed Energy Deposition (DED), and Binder Jetting followed by sintering. LPBF and DED enable near-net-shape fabrication using alloys such as 17-4PH, 316L, Ti-6Al-4V, and maraging steel. These materials can achieve tensile strengths comparable to wrought counterparts after proper heat treatment, but they exhibit unique challenges: internal porosity (0.1-1%), as-built surface roughness typically between 6-12 µm Ra, and microstructural anisotropy due to directional solidification. Binder jetting, on the other hand, offers higher throughput but demands precise sintering control to avoid distortion and achieve full density.

Hybrid Manufacturing: The Practical Middle Ground

Given the inherent limitations of AM in producing precision functional surfaces, hybrid manufacturing workflows have emerged as the most viable path for functional gears. In such workflows, the gear is additively built to near-net shape retaining complex internal geometries or lightweight features followed by conventional machining or grinding to achieve final dimensional accuracy and surface finish.

A typical process chain involves AM → Stress-relief or HIP (Hot Isostatic Pressing) → CNC Machining → Gear Grinding or Honing → Surface Finishing (e.g., shot peening, isotropic polishing) → Inspection. This integration bridges the flexibility of additive manufacturing with the repeatability and precision of subtractive processes. By intentionally designing machining allowances of 0.3–0.5 mm on the gear flanks and root, engineers can ensure that the final geometry meets ISO Grade 7 or better, while still benefiting from reduced material waste and lead time.

Modern hybrid machines that combine DED or LPBF deposition heads with multi-axis CNC milling spindles are gaining attention. These systems can deposit a near-net gear blank and immediately finish-machine the critical surfaces in the same setup, minimizing distortion and alignment errors. Studies have shown that hybrid-finished maraging steel gears can achieve fatigue strengths approaching 90% of wrought equivalents when properly post-processed and heat treated.

When Additive Manufacturing Is Ready

Despite its constraints, AM has proven ready and even advantageous in several practical gearmaking scenarios.

1. Prototyping and Design Validation:

AM excels in the prototyping stage, where the goal is not durability but geometry and fitment verification. Polymer-based AM enables engineers to iterate gear designs rapidly, conduct interference and assembly checks, and evaluate noise and kinematic characteristics at a fraction of traditional prototyping costs. In many R&D labs, functional polymer gears are used for transient torque or NVH testing, where the emphasis is on dynamics rather than endurance.

2. Low-Load, Low-Speed Functional Applications:

Additive polymer gears made from SLS or MJF PA12 and reinforced composites have demonstrated reliable performance in moderate torque and intermittent duty applications such as robotic joints, laboratory automation, and small electric actuators. These environments value customizability and noise reduction over absolute strength.

3. High-Value, Low-Volume Metal Gears:

In sectors such as aerospace, motorsport, and defense, the equation changes. Here, the cost of precision finishing is justified by the gains in part consolidation and mass reduction. One well-cited example is the titanium gearbox produced by Rodin Cars for its hypercar program, leveraging metal AM to achieve complex weight-optimized geometries impossible through traditional forging. After HIP and precision grinding, these gears exhibited mechanical performance close to conventionally machined counterparts. Similarly, aerospace manufacturers have explored AM-integrated gear housings where weight reduction and component integration drive adoption.

4. Tooling and Fixtures in Gear Production:

Even when not directly producing gears, AM has found a solid role in tooling for gearmaking. Conformal-cooled mold inserts, alignment jigs, and customized fixturing systems are now routinely printed, improving efficiency and throughput in conventional production lines.

In contrast, certain application domains expose the remaining weaknesses of AM.

1. High-Torque, High-Cycle Transmission Gears:

Automotive main gears and heavy industrial gearboxes demand fatigue resistance under millions of load cycles. Even a small amount of porosity or surface microcracking can drastically reduce bending and contact fatigue life. AM materials, particularly in as-built or lightly machined states, still fall short of the endurance limits of carburized and ground forged steels. Although HIP treatment and surface finishing improve performance, they do so at the expense of cost and cycle time offsetting AM’s primary advantages.

2. Dimensional Accuracy and Surface Integrity:

The as-built tolerance of LPBF components (±50–100 µm) is inadequate for high-quality gears, which often require tooth-to-tooth variation within ±5 µm. Surface roughness, even after mild machining, can lead to poor lubrication film formation, increased wear, and pitting initiation. Post-processing such as grinding, honing, or superfinishing is not optional it is mandatory for load-bearing gear applications.

3. Repeatability and Scaling:

Achieving consistent quality across batches remains difficult due to variations in powder characteristics, layer adhesion, machine calibration, and build orientation. Unlike machined gears whose variability is well-controlled, AM gears can show significant scatter in microstructure and fatigue life even under identical process parameters. This lack of repeatability complicates mass production and certification.

4. Economic Competitiveness:

While AM shortens lead time for prototypes or spares, its cost per part increases sharply with volume. The finishing, inspection, and qualification steps often negate the time savings achieved during printing. Therefore, AM’s economic sweet spot lies in specialized, low-volume production far from mainstream automotive gear manufacturing.

Technical Barriers and Ongoing Research

The major engineering hurdles preventing AM from fully replacing conventional gearmaking are largely materials and process related. Surface roughness remains the primary challenge. Gears rely on elastohydrodynamic lubrication (EHL) regimes, where the oil film thickness is often less than 0.5 µm. When surface irregularities exceed that threshold, asperity contact occurs, promoting micropitting and wear. Even with post-machining, the near-surface porosity of AM parts can disrupt EHL performance under cyclic loading.

Porosity and lack of fusion defects also serve as crack initiation sites under tooth bending fatigue. Advanced non-destructive techniques such as micro-CT scanning and ultrasonic inspection are now used to characterize and quantify these defects. The introduction of Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) has significantly reduced defect density and improved fatigue life, but its cost and long cycle time limit scalability.

Residual stresses introduced during layer-by-layer melting can lead to distortion during heat treatment or finishing. Computational thermal modeling and optimized scan strategies (chessboard or contour scanning) are helping minimize distortion, while in-situ monitoring and feedback control improve process stability.

Build orientation also affects performance: printing gears with the tooth flanks aligned parallel to the build direction minimizes surface stair-stepping but can weaken tooth-root strength. Hence, design-for-AM guidelines now emphasize orientation trade-offs and sacrificial machining allowances.

Material science plays an equally critical role. Maraging steel and 17-4PH are currently the preferred alloys for AM gears because they exhibit low distortion after aging and good printability. However, their fatigue life still depends heavily on surface integrity and finishing quality. New alloy systems specifically formulated for AM such as cobalt-chromium steels and high-strength tool steels with controlled solidification are under active investigation.

Design for Additive Gears

Designing gears for AM requires a paradigm shift. Instead of directly replicating conventionally machined geometries, designers must leverage AM’s capabilities while compensating for its weaknesses. Tooth-root fillets can be thickened or blended to reduce stress concentration from potential inclusions. Gear blanks can incorporate internal lattice structures for weight reduction or integrated lubrication channels for thermal management. Sacrificial outer layers or ribs may be added to facilitate machining and minimize warpage during heat treatment.

Build orientation, support structures, and machining access must be planned together. The concept of “print-for-finish”, printing near-net geometry with intentional material allowances is now central to hybrid gear design. Combined with simulation-driven optimization, AM allows engineers to create functionally graded or integrated components where conventional methods are infeasible.

Testing, Validation, and Performance Metrics

To validate AM gears for production use, rigorous testing is essential. Mechanical characterization typically includes single-tooth bending fatigue tests, pitting endurance tests, and rolling contact fatigue (RCF) assessments under lubricated conditions. Comparative studies have shown that fully finished AM maraging steel gears, after HIP and isotropic superfinishing, can achieve bending fatigue strength between 80–95% of forged reference gears. However, as-built or partially finished AM gears may fall to 50–60% of conventional performance.

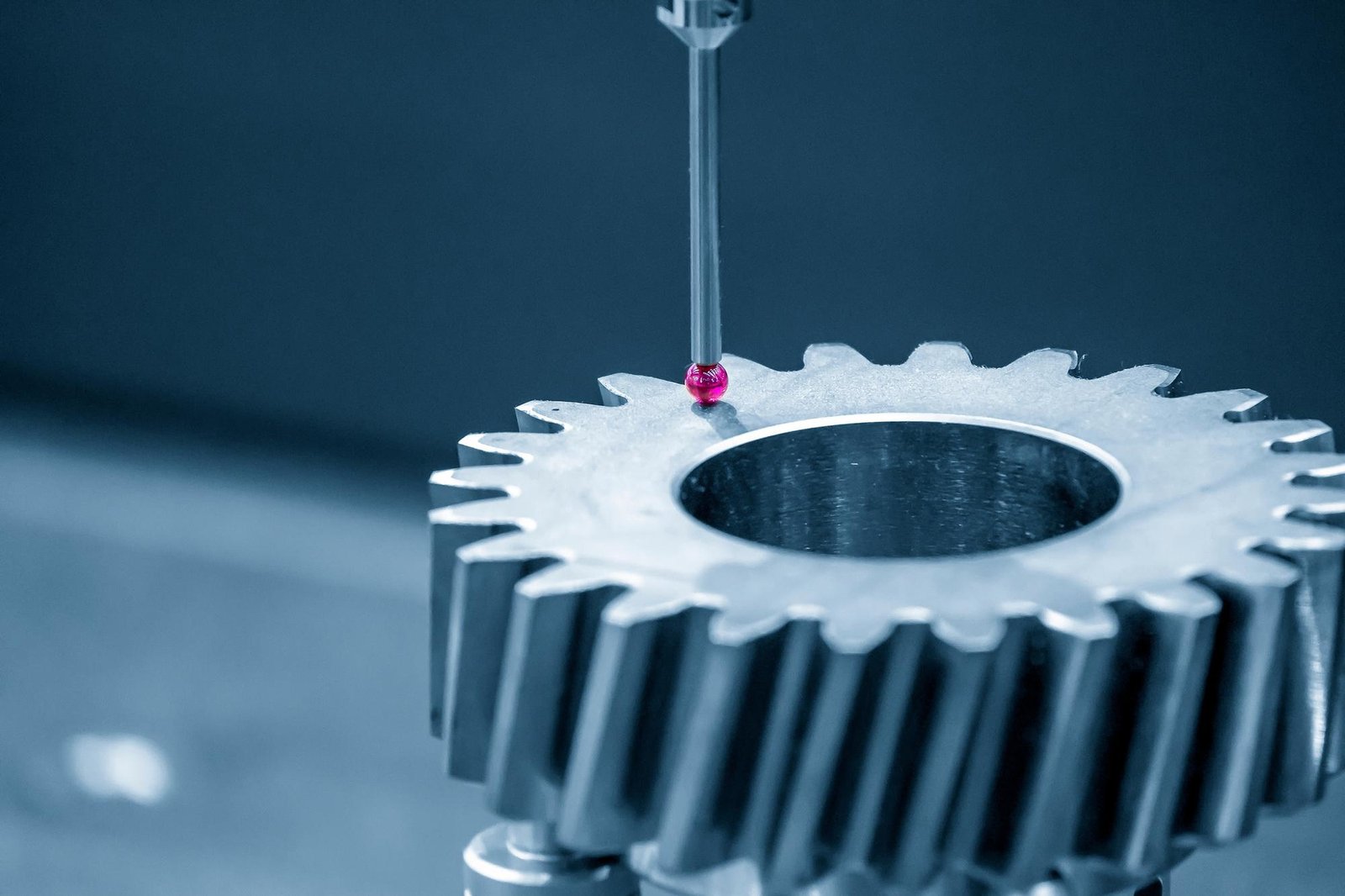

Microstructural analysis through optical and scanning electron microscopy helps link defect morphology to crack initiation behavior. Residual stress measurements via X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirm the effectiveness of stress-relief treatments. Surface metrology, using gear measurement centers, quantifies deviations in lead, profile, and pitch, ensuring conformity with ISO quality grades.

Endurance tests performed on dedicated gear test rigs reveal that AM gears often exhibit higher noise levels and faster wear onset unless ground to fine surface finishes. The combination of HIP, surface polishing, and shot peening remains the most effective route to extend fatigue life.

Industrial Use Cases and Emerging Success Stories

Several organizations are already leveraging AM for gear-related components. In motorsport, where component weight and turnaround speed outweigh cost, AM titanium gears and carriers have been successfully deployed after hybrid finishing. In aerospace, printed planetary carriers and gear housings reduce mass and part count, integrating lubrication passages and mounting features that would require multiple machining operations otherwise.

Research collaborations between universities and OEMs are exploring binder-jet-printed steel gears followed by full-density sintering and grinding an approach that shows promise for scaling production. In tooling applications, AM has revolutionized the design of conformal-cooled molds for gear injection, indirectly improving production efficiency and extending mold life. These examples demonstrate that when AM is integrated intelligently within a hybrid manufacturing chain, it can deliver tangible industrial value.

Future Outlook and Conclusion

The trajectory of additive manufacturing for gears is clear: it is not about outright replacement, but integration. AM will not supplant hobbing or grinding for high-volume automotive gears anytime soon; instead, it will complement these processes by enabling what they cannot complex geometries, integrated assemblies, and rapid iteration. The rise of hybrid systems combining AM deposition, machining, and in-situ metrology represents the most promising evolution in precision gear production.

Future breakthroughs are likely to emerge from three directions: (1) development of AM-specific alloys optimized for fatigue resistance and low defect sensitivity, (2) intelligent monitoring systems that provide real-time quality assurance, and (3) automation of post-processing and finishing to reduce cost. As material databases expand and hybrid workflows mature, AM gears will gradually transition from experimental curiosities to fully qualified components in specialized, high-value systems.In short, additive manufacturing for gears is ready when it is hybridized, validated, and intelligently applied. It remains not ready for commodity-scale gear production where speed, cost, and proven reliability dominate. The future of gearmaking will likely belong to those who understand both the strengths and the boundaries of this technology and can combine them with the century-old precision of conventional engineering.